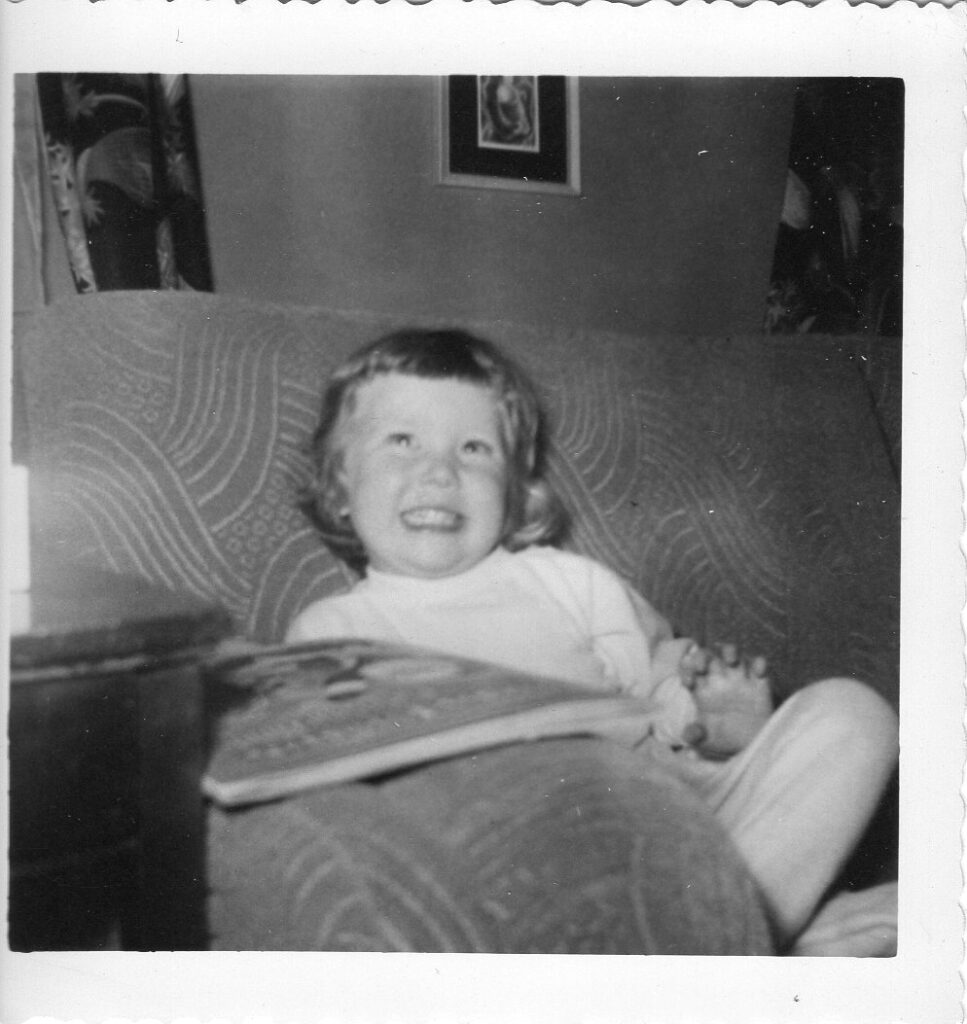

When I was around three years old my father was still a coach at Gettysburg College, as I recall, although by then he might have already accepted a job in the admissions department. As a coach he worked with many different teams at different times: men’s swimming; men’s wrestling; women’s basketball; and his first loves – baseball and football. He acknowledged that he didn’t know much about either swimming or basketball, but did his duty to fill in where needed with those teams. He also knew how important it was for kids to learn to swim at an early an age. As a coach he had the privilege of a universal key to all the college athletic facilities and knew when the swimming pool was closed. I recall many Saturdays and Sundays in the winter being escorted across campus to that dark, musty, echoey, chlorine-smelling old aquatic center with my sister when it was empty so that we could ultimately be the youngest children ever in south-central Pennsylvania to swim 20 yards unassisted. Dad’s instruction techniques were raw but effective. While one of us would watch from the edge of the pool he would clutch the other securely and walk out to the middle of the shallow end of the pool. “Swim to me,” he would encourage, while releasing whichever one of us was the unwilling student, and taking one step backwards. As I recall, and I’m sure it was no different for my sister, as I made the single doggy paddle stroke to his waiting hands, expecting to be picked up and brought tightly to his congratulating chest, he took a step backward and I was forced to gasp for air, put my face back in the water, and struggle for another several feet until I reached him again. He would repeat this pattern as many times as he determined safe, working his way up to the point where we could each swim from the middle of the pool to the edge without assistance. Since I was younger I got to observe my sister reaching this milestone at least a full season, probably two, before I did. But by the time I was four I could easily swim the entire length of the pool without assistance, and my sister, by then a first grader, was the equivalent of a four-gaited horse, having mastered the crawl, the backstroke, the breaststroke, and the butterfly. She was also fearless off of the three meter diving board, but I would not climb those scary steps until the following season.

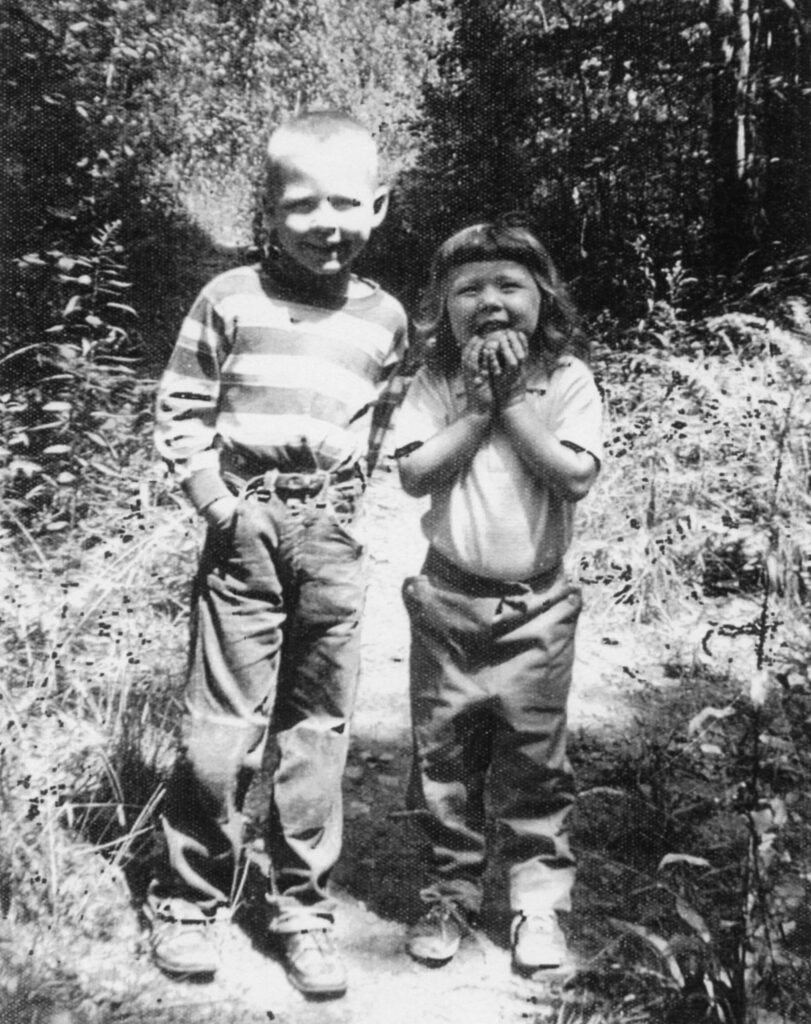

The summer that I turned six, 1956, my father took a job as a water safety instructor and baseball coach at Camp Susquehannock in Brackney, PA, just across the state line from Binghamton NY, on the shores of Tripp Lake. As I recall it was a wonder-filled summer for me, but many years later my mother, who was caring for an infant daughter, confessed it was less than pleasant for her. I loved the rustic, rural setting. We stayed in a cabin with no electricity or plumbing. We could use either the outhouse or the chemical toilet, our refrigerator was kept cool with a block of ice that was cut from the frozen lake the winter before, and if we weren’t in bed by dark we relied on battery-powered lanterns and flashlights. I don’t remember how my mother cooked, or if she cooked, but I think the stove simply burned wood and vented the smoke through a stovepipe. Most if not all of our hot meals were enjoyed in the camp’s mess hall. She did, however, take delight in walking with her friend on several occasions up the stream bed that fed the lake to a pool created by a beaver dam. There she would sit for as long as her infant daughter would remain still to read and watch for beavers as they appeared from time to time above the surface of the water. I spent the first week of that summer in crafts classes making lanyards out of gimp string, wandering through the expanses of forests with my younger sister (we loved thinking we were lost in the wilderness on those trails through the woods, when in fact we were probably always within shouting distance of responsible adults), watching the campers play baseball (baseball and water sports were main features of the camp) or hanging out at the lakeside docks watching the campers learn to paddle canoes and row boats. I wanted badly to take a canoe or rowboat out on the lake by myself, but was told in no uncertain terms that I would have to wait several years before I could. Before anyone could solo in a boat he or she had to swim across the 1/2 mile lake unassisted. No one under the age of eight had ever done this. I was still a month shy of six years old.

As the water safety instructor my father got to proctor campers as they underwent the test to prove they were worthy of piloting a canoe or rowboat by themselves. This entailed accompanying them in a rowboat as they swam the length of the lake. To keep me entertained my father let me ride with him in the rowboat for several of these tests. From the perspective of the rowboat the lake didn’t seem that long, so I began pestering my father to let me try to swim it. He, of course, declined repeatedly, until one of the college-age lifeguards working at the camp for the summer bet my father (I don’t know if there was an actual wager) that if he let me try I would be able to do it). So the next morning with my father in a rowboat to one side of me and a college student lifeguard in a rowboat on the other side I began my challenge of doggy paddling the entire length of Tripp Lake. I don’t really remember if the effort seemed hard or not, whether I needed encouragement or not, or how I felt at the end, but I do know that I completed the swim in very unstylish form without any assistance. According to my father I was recognized that night at the mess hall dinner as the youngest person to ever swim the length of the lake unassisted. My older sister, a much better swimmer than I, swam the lake the next day, probably in half the time it took me. We both enjoyed rowing and canoeing around the lake by ourselves for the rest of the summer. As an aside, my father told of how they held swimming competitions at the camp and back then Susquehannock was for boys only. My father signed my sister up for several freestyle and backstroke races against boys her own age and she won every one. My father was the star of one faculty baseball game when Susquehannock played the staff of another nearby camp and he hit a home run late in the game for a come-from-behind victory. It was a ground ball home run that managed to squirt between first and second base, between the right and center fielder, and roll down a hill into the weeds and the trees at the far edge of the outfield.

We returned to Camp Susquehannock the following summer but without my younger sister Beth, who had died from the flu the previous November. Whereas the previous summer we had been a happy family gaining attention for noteworthy achievements, people who knew us from the year before might have wondered if we were the same individuals. My mother had become reclusive, barely venturing out of our cabin, with one sad exception. When not busy with his instructor’s duties my father retreated to our late model Oldsmobile trying to catch as many baseball broadcasts as he could through the static on the car radio. I hardly remember by older sister that summer – I can’t even say for sure that she was with us then. I was lucky to have been taken under the wing of the camp doctor, who was also an amateur ornithologist and astronomer. He made me aware of the North Star, the Big Dipper (Ursa Major) the Little Dipper (Ursa Minor), Cassiopeia, the Pleiades, and a comet that appeared in the sky the week we were leaving to go back home. He also loved the birds that were native to the area, and could identify them by song, by flight pattern, and by silhouette. My mother’s single anticipated joy that summer was to revisit the beaver dam where she has spent such pleasant hours the year before. Hiking up there again with her youngest daughter, who was now a toddler, she found the site had been cleared for development and had been reduced to mud, felled trees, and bulldozed earth beside an exposed creek bed. There was nothing that remained of the beavers, their dam, or the pristine pool that had formed behind the dam. I recall that she wrote a touching story recounting the year of her child’s death, culminating with her discovering of the destruction of her site of refuge. My only memory of the lake from that year is of my other young sister, who still bears the scars on her chin and below her bottom lip, taking a fall off the dock overlooking the shallow water at the edge of the lake and the rocks below. I’m not sure how a toddler managed to wander out there unnoticed.

The following summer my family and another rented a house on a remote beach in Rhode Island. My memories of that summer are not as vivid, but I recall being more withdrawn, having lost my desire to take on challenges or seek new thrills. I wanted to study the sea but I didn’t care so much about being in it. I listened to some of the local men talking about wave patterns. They explained how waves tended to come is sets of three large waves, then there would be a lull of six small waves, then another set of three. If you watched the big set, usually the third wave of the set was the biggest, and it broke the farthest out. I recall one day some boys a few years older than I were playing in the waves, enjoying being tossed around and splashing each other. My father encouraged me at first to do the same, but I wasn’t interested. I preferred watching the waves, the sea gulls, and seeing what the fishermen were catching with their lines cast out over the breaking waves. After a while he became annoyed with me and seemed to give up. I was scared of the bays behind the sand dunes from where we watched the waves. The other family we vacationed with had an older boy and an older girl. Both were closer to my sister than to me. The boy and his father took their dinghy into the bay to fish and because the water was shallow sometimes ended up wading. They talked of crabs and lobsters in the bay, and came back with cuts on their feet from crab pinches. I wanted no part of that. It reminded me of a small cove on Tripp Lake at Camp Susquehannock where it was said a snapping turtle lived. It was a spot to be avoided at all costs. The turtle was alleged to be at least three feet long and known to have taken toes off campers. For a short time in my life I was afraid of these creatures, along with the copperhead snakes that were supposed to infest the tainted soil and the haunted battle fields of Gettysburg.

There was a piano in the house we rented on the beach in Rhode Island, and I remember my sister and the daughter from the other family singing “Barbara Allen” while playing that old upright over and over again. It really made me want to learn a musical instrument. Later in life, as a young teenager, I did take up the guitar, much to my father’s disappointment and objections.

The cottage had a clay tennis court on the property, and my father and the father in the other family were both excellent tennis players. The court was a primary reason for choosing this site. When everybody wasn’t by the water my father and the other father were playing tennis. I never understood, as much as my father loved tennis, and as much time as he devoted to it, why he never took the time to share his love of the game with me. From the time I could walk he was trying to mold me into the next switch-hitting Mickey Mantle, or teach me how to hold my arms to take a football hand off, or how to properly tackle a ball carrier, but he never wanted to share his interest in tennis with me.

While we were in Rhode Island a hurricane formed off the Atlantic coast and generated rough storm surf along the New England shore. We all walked down to the beach the morning that the waves were predicted to hit, just to witness the amazing natural spectacle. Several young men were out swimming in the breakers. I recall one with swim fins on who was quite skilled at swimming toward shore as a wave reached him when it was cresting but before it had broken. He was able to slide down the face of the wave and angle to the side and outrace the breaking part of the wave for several seconds before diving down and seaward as the entire wave closed out in one huge explosion of white water. Others seemed to be trying to do the same thing but most were not able to get up enough speed to slide down the face, and the wave passed them by. One poor guy got caught at the top of a wave just as it broke and he got thrown out and down what must have been a twelve foot face along with tons of white water, onto shallow water and sand below. He staggered from the water and walked past us on the beach, looking like someone who had just walked away from a head on collision. My father said something to him and he replied, “Man, I had no business being out there.” The next instant, my father saw another swimmer in the water who appeared to be in trouble. My father threw off his sweatshirt and sandals and charged into the manic surf, only to struggle out of the water five minutes later on hands and knees at the edge of the shore, barely able to catch a breath. While none of us on the shore ever thought he was in serious trouble, he later confessed that he did not think he was going to make it out of the water alive that day.

Over the next seven years my life changed in many ways. After my parent divorced I stayed with my father in Gettysburg while my sisters and mother moved to New Jersey. My father arranged for me to work out with the Gettysburg College swim team after school for two consecutive winters to keep me out of trouble when I wasn’t playing football or baseball. I became a much better swimmer than I was a football player or baseball player. My father became somewhat of a womanizer in our small town, and when he wasn’t with one the widows, divorcees, or single women in Gettysburg he was hanging out at the Peace Light Inn, a classy bar, with his single coaching friends, me in tow (usually on a school night). I also spent a lot of time alone during this period, and had purchased a Silvertone guitar and was learning a few chords so I could play a few rock ‘n’ roll and folk songs. This seemed to aggravate my father to no end. By this time he was Dean of Students at the college, but he had fallen out of grace with the college President, so we eventually moved to Southern California to live with his sister and her husband while he waited to find work and recover from spine surgery. This was 1965. The Watts Riots were happing, the Viet Nam War was escalating, the Beatles had taken over American radio air waves, and Bob Dylan had gone electric.

One day in September a few weeks after we had arrived, my uncle decided we should all go to Newport Beach. My father was in a back brace and walked with a cane, still in quite a bit of discomfort from his surgery. I had not yet seen the Pacific Ocean. The radio reported a strong south swell from storms off southern Mexico, but the weather in Orange County could not have been more perfect. I had seen photos and videos of the Pipeline on the north shore of Oahu, Hawaii, but had never seen big ocean waves other than the choppy, white capped, formless waves in Rhode Island many years ago. When we got to the beach that day I saw line after line of waves coming in from the sea, and when they approached the beach each one formed a series of peaks up and down the beach. As these peaks broke each one tossed a mane of whitewater curling out in front that peeled off in both directions like a woman’s hair being released from a curler. The water, other than the waves, was as smooth as the surface of a mirror. There were some surfers in the water, but it wasn’t overly crowded. I had no idea this was a very rare event for Newport Beach, and would not likely occur again for years. I said nothing to my father, my aunt, nor my uncle, but dropped all my belongings next to theirs and headed across the sand, running into the water and those perfect eight to ten foot waves to take my chances as a body without an apparatus in the water with board surfers and belly boarders.

Two things worked to my advantage that day. I had learned a lot watching the waves in Rhode Island and listening to the men on the beach, and I had become a strong swimmer after two years of working out with the college swim team. I didn’t know at the time how much consternation I was causing my father, who felt helpless in his condition, worrying that I might be drowning in a violent sea while he was disabled and helpless on the shore. My father, about whom my mother used to say had a hero complex. I had the time of my life during that hour in the water, catching wave after wave, feeling myself moving with the sea, feeling like I was harnessing the energy of the waves, feeling like the waves wanted me to be a part of them. I was not prepared for the anger I encountered when I got out of the water. I was not prepared to have to begin thinking about the person my father had made me after my sister had died, and how he blamed me for the worry I caused him whenever I did things that normal adolescent boys did. I began to see that there was a pattern in my father’s approach to me, just as there is a pattern to the waves in the ocean. Sometimes the seas are stormy, sometimes the swells are big. Sometimes they bring pure joy, sometimes they take you to the edge of death. Until you understand, you don’t know how to ride.

There is much more to be said about my father and me. Perhaps I will devote other posts to the subject, perhaps not. I am fortunate that in spite some very difficult years during my adolescence and early adulthood we spent the last thirty or so years of his life on good terms, never really resolving the earlier times but able to leave them behind.