It’s been six weeks since George died after a little over a week in the hospital and two or three days in hospice. I’ve put together several pages of videos and songs in his memory, but I’m writing this now to explore my reaction to his dying and his death, and to reflect on how he chose to live out his final few months. I hope it will serve to also remind me that the way I choose to handle my dying, if I have a choice, affects others.

My mother died at the age of 84 in late November of 2012. She let everyone she was close to know that she had cancer of the esophagus soon after she was diagnosed, and when she knew her death was imminent, she wanted my sisters and me to be with her for her final weeks. In her last six months she enjoyed as much time as she could with her children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren, and enjoyed travels and other activities as her health allowed. In this way she celebrated her life with those around her, and together they reflected on it in a way which helped make it complete.

My father died barely a year later. His dementia sometimes prevented him from knowing where he was. I had moved him from California to a memory care unit in Denver where my wife and I visited him almost daily in his last few months, and his daughters and grandchildren were able to visit during that time. He usually recognized us, but was often disoriented otherwise. The time we spent with him allowed us to come to terms with his passing, but his compromised cognitive state robbed him of the chance to acknowledge the ending of his life in a way that was meaningful to him. It seems a great tragedy to not know who we are or who we have been as our lives are coming to a close.

My wife, Leslie, was diagnosed with a brain tumor less than three months after my father died. She immediately reached out to her brothers, friends from high school, college, nursing school, previous jobs, and many other people who had meant something to her at different stages in her life. Her response to treatment was positive and we were sure she would be one of the rare people who survived many years with a glioblastoma, but sadly she took a turn for the worse a year after surgery and died on March 31, 2015. Up until then we traveled to New York, New Mexico, and California, and welcomed many visitors into our home. She ran foot races with her son, step daughter, and daughter-in-law, rode a bicycle through the Colorado and New Mexico mountains, swam in the Pacific Ocean, and sang songs with her friends. She died after spending her last year visiting and sharing good times with the people she loved, and allowing them to love her in return. Leslie wanted to die at home and I did all could to make this happen, but we reached a point where I was not able to manage her pain. Many friends were with her in a local hospice facility during her final week. Lukas, her son, had been with us at home the week before in Denver, but had to return to Albuquerque. When he got word that she was in hospice he rushed back to Denver, but by the time he arrived she had been comatose for nearly two days. There were a handful of us in the room when he entered. We all observed a visible reaction on Leslie’s face at that moment. I’ve related this event often, as I think about the power of love, the nature of consciousness, and how we should not make assumptions about things we can never understand. I’m reminded of it now, thinking of how George spent his final days.

I’m not sure of the timeline, but I think it was less than two years later, at a concert at Red Rocks, when my good friend David told me that he had just been diagnosed with lung cancer. He said there were treatments that could probably keep him relatively symptom free for several years, but the disease would ultimately prove fatal. From that date until Covid-19 forced us all into isolation, we enjoyed bike rides, hikes, and concerts together. One especially fun event was a cabbage-chopping party Nichole, his wife, organized as part of her preparing a large batch of sauerkraut. This event brought together friends, neighbors, and relatives. David loved the Grateful Dead, Frank Zappa, and the jam bands and other groups that carried on their traditions. He and a group of his friends would get together for dinner, beer, and concerts to see Phish, Dead and Company, Phil Lesh and Friends, Dweezil Zappa, and other artists. When Covid-19 hit David had developed a chronic cough but still was strong and feeling healthy, but we didn’t see each other. A year and a half later I got a call from David asking me to meet him outdoors at Sloan’s Lake. When I got to the agreed-upon meeting spot I found him in a wheelchair, looking frail, and dependent on Nichole for mobility. It brought back memories of Leslie’s final days before she went into hospice. Tragically, Covid-19 had robbed David of the comfort of sharing time with those he cared about and those who cared for him. Like my mother and Leslie, and to some extent my father, he wanted the time between his diagnosis and his death to be enriched by sharing it with the people he cared about, and doing the things he loved.

Of the four people with whom I had been close between 2012 and 2022 that I had accompanied up until their deaths, Obviously I was closest to Leslie. I was privileged to let her show me and the others around her how much life meant to her, and how much the people in her life meant to her. She freely allowed us to tell her and show her how much she meant to us. Not only did she demonstrate and express her love for life itself, but also how much she valued the life she had lived and those who had shared her life with her. The experience of having lived is different in some ways from the essence of being alive, and I watched this play out in hearing her recount, sometimes in the presence of and sometimes not, those who had shared those experiences. In a sense, knowing that she was losing her life gave her the chance to enrich the lives of those who would survive her.

I just heard that Peter Schjeldahl, a long-time art critic for New Yorker magazine, has died. In 2019, when he learned of his diagnosis of lung cancer, he wrote an essay called The Art of Dying. In fact, it was much more than an essay. It was a memoir – a reflection on his life. I started writing this piece about George several days ago and was about to give up on it when I started reading Schjeldahl’s piece from 2019. I have read many of his articles in the New Yorker in the past and often found his writing irritating. I wondered if it annoyed me because as an art critic, he did not consider me, a naive reader, to be his intended audience. I would read his articles hoping to learn more about modern art, but found that he was writing for people who were already there, people who knew the world of modern art very well. But his writing was also very clever – so clever that I thought he was showing off – not so much trying to communicate as he was trying to impress. The truth was probably that his writing was so brilliant that it was too challenging for me. I struggled to make sense of his metaphors, similes, and analogies. The Art of Dying is, in contrast, an honest, touching, amusing reflection on his regrets, achievements, insights, and other personal observations that one might be expected to have upon learning of a terminal illness. Reading it has further helped me to understand why George’s dying and his choice in dealing with it has left me, six weeks later, still coming to terms with it.

I met George in late 2015 or early 2016, when I decided that joining the Acoustic Music Community and taking part in open microphone events would be a way to help me cope with my own grief. For those who might not know, an open mic is an event where musicians, comedians, and storytellers, who for the most part are amateurs, can sign up to sing a few songs or otherwise perform in front of a crowd at a coffee house, library, church, or brew pub. The first one I attended was at a brew pub where I sang a song I wrote and also sang an old Bob Dylan song. George approached me afterward and said he liked my guitar playing and my choice of songs, and thought perhaps I could back him up in the future on some songs he’d like to sing. Through George I met nearly a dozen other amateur musicians who have come to be good friends, and I give George credit for helping me find a new focus for my music. Together we worked out a half dozen or so songs that we performed at various venues and events over the next several years.

The way George and I met was the way George had met everybody else that I came to know through him. As far as I know, the only friends George had were friends he had met through his interest in music, which centered on folk singer/songwriters on the 1960s and 1970s. George was opinionated. If he liked a song, he liked it very much. If he didn’t like a song, he didn’t want to hear it, didn’t want to consider singing it, and didn’t want to hear anybody else sing it. There were aspects of the singing and playing of each of his friends that he appreciated, but he was very specific about each of our shortcomings, as well. If he asked one of us to play guitar or piano for him on a song he wanted to sing, he was quick to tell us when he didn’t like how we played it, although he couldn’t always articulate what we should do differently. Although he was a good enough guitar player that he could accompany himself on most songs he liked to sing, he preferred not to play when he sang.

George said at least once that it was impossible to play a song too slowly. He preferred ballads by Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Richard Thompson, Lennon and McCartney, Phil Oaks, John Prine, and Townes Van Zandt that allowed him to show off his ability to reach high notes, and he liked to slide into those notes, then hold them in long, drawn-out hums. Not everyone appreciated his style but it was distinct and some – many, I think – found his singing very moving.

Some of George’s opinions were fixed and firmly held. He and I agreed that we liked Bob Dylan songs from the mid 1960s, especially from the albums Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde. But there were times when I would bring up a song that I liked, expecting him to agree with me, and he would tell me in no uncertain terms how wrong I was. It was just as likely that if I criticized the same song he would defend it. These exchanges didn’t consist of debates, but rather George’s matter-of-factly expressing what was the correct position to hold on the merits of the song.

Several of us worked with George to put together performances of three hours each. George selected the music and had the most input into the arrangements, and for the most part they went well. There was one that was different. I was working with him on another performance about a year ago but backed out when rehearsals became contentious and time consuming. It was partly an issue of his not liking the way I played an accompaniment. He would stop me midway through the song, saying it wasn’t right, but he wasn’t able to explain what he didn’t like. And he started expanding the scope of the performance. Not only was I expected to back George up on guitar and add harmony where possible, but I was to provide the sound system and make adjustments to the balance, volume, and equalization with each number. As he brainstormed other performers he wanted to include in the event, I realized I would not be able to manage everything. What I thought was going to be a simple evening of George and me together had turned into a rotating list of five or six different acts over a three-hour time period. I don’t think he ever forgave me for backing out. But now I think I understand what was going on in him mind, even though he never explained it to me. He probably never understood his unconscious motives himself. The others George intended to include were people whose talents he had come to love, and I think he wanted to, in his way, let them know how much he appreciated them, and also give himself the gift of having them perform for him. Although I didn’t know he was dying, he did. He was planning a celebration for himself. I believe he was more accepting then of his mortality than he came to be months later.

More than two years earlier, when the pandemic first hit and we stopped meeting in person to play music, I began hosting song circles on Zoom. George joined enthusiastically and helped me pick a list of people to invite to participate on a weekly basis. For over a year we shared songs every Wednesday evening from 7:00 pm until 10:00 pm. After that we decided to only get together once a month. Looking back now, I can see that George had a reason for picking the songs that he chose to sing week after week. It wasn’t so apparent at the time.

One of his favorites was Carrickfergus, a song written by Dominic Behan that was popularized by the Chieftains, and includes the lyrics:

But I'll sing no more now til I get a drink.

I'm drunk today and I'm rarely sober,

A handsome rover from town to town,

Ah but I'm sick and my days are numbered,

So come all ye young men and lay me down.

He also liked to sing Kate and Anna McGarrigle’s Talk To Me of Mendocino:

. . . and let the sun set over the ocean,

I will watch it from the shore,

Let the sun rise over the redwoods,

I'll rise with it til I rise no more.

I was not familiar with Sandy Denny’s song, Like An Old Fashioned Waltz, when he sang it one night, but it, too, contains lyrics hinting at death (or perhaps immortality):

How I'd love to remain

With the silver refrain

Of an old fashioned waltz,

As they dance round the floor,

And there's no one else there,

And the world is no more.

On a different night he sang a song by Danny Flowers, James Hooker, and Nanci Griffith called Gulf Coast Highway with the lyrics:

And when we die we say we'll catch some blackbird's wing

And we will fly away to heaven

Come some sweet blue bonnet spring.

And George was always game for singing a Bob Dylan song. Forever Young was his favorite, but he surprised us one night with Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues with these lyrics:

I don't have the strength to get up and take another shot,

And my best friend, the doctor, won't even say what it is I've got.

Toward late 2021, George started joining less frequently. He had undergoing bypass surgery a few years previously and suffered from COPD, and cited breathing difficulties sometimes as a reason for not joining. I was surprised one night in June when I reminded him of a scheduled Zoom meeting, only to hear from him that he was in the hospital. I went to visit him the next day and he told me that another friend, Lonny, whom he had known since the 1970s when he lived in Cincinnati, had been keeping in close contact with him and when George had stopped answering his phone Lonny had the police make a welfare check on him. They found him nearly unresponsive in his apartment and had him taken to the emergency room. It was during this visit in the hospital that George told me that he had metastatic prostate cancer (it turns out he had been diagnosed many years earlier), but made me promise not to tell anyone. He said that Lonny and I were the only ones who knew. He intended, he said, to let the rest of our circle of friends know in person when the time was right.

Two weeks later George was transferred to a rehabilitation facility where they hoped to get him well enough to return home. I tried to visit him there but because I had been exposed to someone with Covid I was not allowed in. More than a week later, when he was transported home, he asked me to meet him at his apartment because he didn’t think he would be able to negotiate stairs. He told me then that he thought he had between six weeks and three months to live. I was still asked to keep his condition to myself. In the mean time, he hoped to put together a list of all his friends he had heard perform or who had performed with him, and note the songs that he thought they performed the best. He intended to share this list. He never did. Again, he told me that he planned to tell everybody in person his his condition when the time was right. I urged him to change his mind and tell people immediately. I knew people would want to know and would want the opportunity to visit with him, and that he would benefit from their company. He never did.

I had been dismayed at the condition of his apartment. It had been nearly a month since he had been there, and clearly he had not been able to manage for a long time before being taken to the hospital. I offered to pay for a professional cleaning but he assured me he would be hiring someone to get it back into shape. He never did.

Another week went by, and I received a call from George. He had a prescription for pain medication that he wanted me to pick up for him. He was barely able to rise from his chair, so driving was out of the question. I could hear voices in the background. He told me that a home health team was making a visit. Several hours later I delivered his pills. The apartment was in even worse condition than before. He told me the home health team would be back in a few hours to take him to the hospital. I was relieved, and asked him to contact me when he was admitted. Two days later, on a Saturday afternoon, I called the hospital and they had no record of his being there. I called his doctor’s office and they would not give me any information on his condition or status, but apparently my call triggered a welfare check to his apartment. He was found nearly unresponsive again, and taken to the hospital. I found out later that the team that was at his apartment when he called me was there to take him to the hospital, but he refused to let them take him.

The following day I received a call from the hospital social worker who was hoping I might have some information on George’s next of kin, power of attorney, and end-of-life wishes. It seems he was being combative, insisting that he didn’t need to be in the hospital, and expressing anger with me for making the call that resulted in his being there. He wanted to be discharged. I knew George had no siblings or children, and he never talked of any other living relatives. At one point the social worker and his attending physician got me on the phone with George where I was encouraged to talk sense into him, but he became angry with me, so we ended the call. I thought perhaps this would be the last contact I had with him.

The next morning I was several miles into a bicycle ride when my phone, mounted on my handlebars, rang. The caller ID said it was George. As angry with me as he had been the day before, and as disoriented as he had been, I did not think he’d be calling me. I expected it to be a hospital professional calling on George’s phone to inform me of a crisis, or worse. Instead it was a calm, lucid George sounding like his old self, taking his time finding the right words, slow to get to the point, repeating himself, getting distracted and asking questions off topic, but sounding like the George I had known these past six years. When I realized the call was going to go on for a while I moved out of traffic into a shady, secluded spot and listened to him ask me to help him invite all his musician friends into his hospital room that evening to play for him.

Amazingly, ten of us were able to mobilize on short notice and take guitars, autoharps, mandolins, and a bass ukulele into his hospital room and play whatever songs he requested of us from 6:00 pm until 9:00 pm. George was happy that night, but not well enough to play or sing himself. I kept think that if he’d have let people know months ago that he wasn’t well we could have had dozens of events like this. As it was, most of the people there that night didn’t know he wasn’t going to get better. The following Saturday he was admitted into hospice. Several of us visited him the next day. As my friend and I approached his room we could hear him groaning in pain. The nurse told us his dose of medication had just been administered. We sat with him as he tried to speak but was unable to make himself understood. As the medication took effect he became still and quiet. We left when it appeared as though he had fallen asleep. He died the next day, September 5, 2022.

His healthcare providers had asked him if he had designated anyone to have power of attorney. On the first day of his second hospitalization he told St. Joseph Hospital that Alan, a friend in New York from many years ago, had power of attorney. Alan was contacted and said that although he was willing to accept the responsibility, no documents had ever been signed. Then George said Lonny was actually his power of attorney. This, too, was not correct but the following Wednesday the necessary documents were executed to make it so, although George had trouble accepting that it needed to be done.

George would not say what he wanted done with his remains. Lonny tried to get him to express his wishes several times, but his unwillingness to answer seemed consistent with his denial that his death was imminent. This was similar to his thinking that the right time would come later on to tell people of his condition. When he died without having made a decision his body became the responsibility of the state. This means there is no grave or other memorial site.

My mother gave her body to the University of Minnesota for research, but we were given her cremated remains eventually. My sisters and I, along with our spouses, held a ceremony at Solana Beach in California, a favorite vacation spot of Mother’s, where we sent her ashes floating out to sea. My father was also cremated. We held a small ceremony at Seal Beach to offer his ashes to the Pacific Ocean. Leslie, too, was cremated. One third of her ashes were buried at the base of a memorial tree in her hometown of Voorheesville, New York, one third at the base of a memorial tree by Sloan’s Lake in Denver, and one third at the top of Lookout Mountain, one of her favorite cycling destinations. I can think of my parents when I think of or visit the west coast of the US. I often ride to the spot where I distributed Leslie’s ashes on Lookout Mountain, and I end most of my bike rides by stopping at Leslie’s memorial tree by Sloan’s Lake. George has no spot that holds any physical remnant of him, where any of us can go to remember him.

I’ve tried different explanations for George’s handling of his own terminal illness. One is to tell myself that, although he kept up the appearance of a rational person through most of it, he wasn’t really rational. Maybe he thought, in some unconscious or unstated way, that if he didn’t tell anyone he was dying, then he wouldn’t be giving nature permission to take his life. Telling people you were dying was letting nature know it was true, but keeping it quiet was to keep the fact at bay. Likewise, nature couldn’t have its way with you if you stayed out of the hospital. Nature couldn’t shut down your organs if you didn’t put your initials on a piece of paper expressing your wishes for what to have done with your no-longer-functioning body.

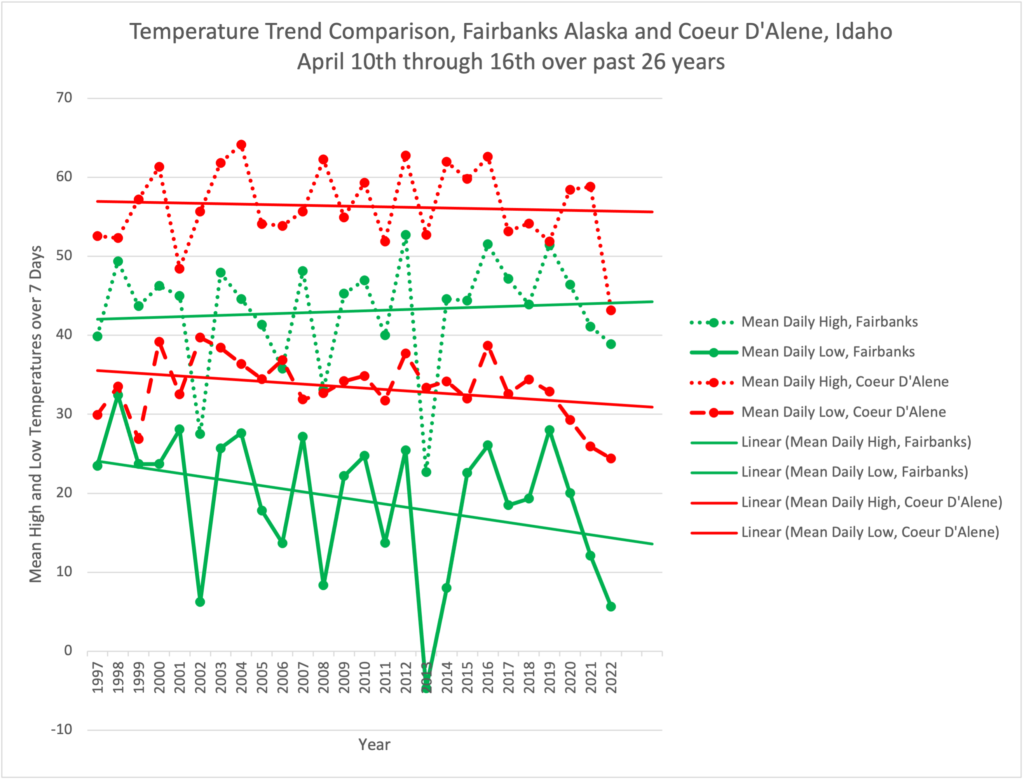

This sort of made sense with regard to his behavior in his last few months of life, but looking back at the songs he chose to sing a year or two before that, he seemed to be more accepting of his mortality. Maybe knowing that he still had several years to live made the prospect of death easier to accept. I don’t know how long he had been on pain medication, but the prescription I picked up for him was a strong narcotic. Who knows how that might have been affecting his cognition and reasoning.

When we tried to get George to give Lonny permission to take responsibility for his car, at this point five days before he died, he asked three of us individually if we thought he would every drive again, and when we said no he argued with us. The Sunday before that, when I was advised by his caregivers that anyone who wished to visit with him might only have several days left to do so, George was arguing that it was being in the hospital that was keeping him from hearing live music, driving around town, and attending fun events. In reality, he hadn’t had the strength to walk across his living room. I wonder if this kind of thinking hadn’t taking over his mind months before.

Why had George been so different from my mother, my wife, and Peter Schjeldahl, who, knowing they were dying, wanted to relish every remaining moment with friends and loved ones, and reflect on the lives they had lived, honoring both the blunders and moments of pride? Unlike David, who had the opportunity to do so robbed by the pandemic, or my father, whose dementia kept him from being aware of how his life was ending, George could have celebrated himself and allowed those who cared about him to join in that celebration. Now he’s gone and he’s left many of us feeling we didn’t help him through the end of his life properly. I have friends who have lost spouses or loved ones suddenly, to heart attacks, strokes, or accidents. They didn’t have time to prepare for this loss. I suppose going suddenly is a blessing in that there is little or no suffering, but those who are left never have a chance to say proper goodbyes, settle unresolved issues, apologize, ask for forgiveness, forgive, or say “I love you” one final time.

George had to opportunity to let the people close to him know how he felt about them, and for them to let him know how they felt. Instead he died angry with those who tried to help him, and he left them feeling angry with him for not letting them help, and for not letting them be close to him as he was losing his life. It was his life. It was his choice and his absolute right to make that choice, but unlike the other deaths of people I’ve loved, his is an unsettled one. There is no summary or conclusion to be reached. George’s behavior dealing with both music and illness is easy to describe, but hard to understand. Was he private and aloof because he didn’t want people to truly get to know him, or is the George we saw all there was to him? Was he sometimes disagreeable and contentious because it was a way he could flatter himself, or was he just confused and inconsistent? Maybe beyond the way people made him feel when they sang and played instruments, he had no feelings for others. Maybe his friendships went no further than asking someone to play a few guitar chords behind him when he sang, or no further than feeling special if asked to sing some harmony. Many of us are left to wonder.