I’ve been listening to a radio broadcast about Mitt Romney on which Romney said his actions as a Senator were motivated by “an oath I took before God.” When I heard him say this I had to admire him for being true to his values. Unlike most Republicans today, I don’t think Romney is a hypocrite. But at the same time, his statement implies that he acts the way he does because in the end he believes his life and his actions will be judged by God. But our actions and our decisions have immediate consequences. Do religious people really base all their decisions on the promise of an eternal reward in paradise? Don’t honesty, justice, kindness, and charity exist independent of a supreme being? Don’t humans have enough common sense to know how to act in ways that serve the greater good here on Earth while we’re alive, without consideration of a payoff in the afterlife?

According to Exodus, God gave Moses the Ten Commandments to share with the Israelites after God had helped them escape from Pharaoh and the Egyptians (subsequent to God’s hardening Pharoah’s heart and sending plagues upon the Egyptians). But only Moses was permitted to meet with God, who promised death to any who set eyes on his face, or even ventured above the boundary he had set at the foot of Mt. Sinai. This is strange behavior for a loving and benevolent God, and forced Moses’ followers to trust him that the words he was sharing were actually the words of God. This isn’t so different from Evangelical preachers today who tell their congregations that God speaks directly to them, telling them what he wants the congregants to know, to believe, and to do. Perhaps Moses used his own judgment to devise the rules he wanted the Israelites to follow, but didn’t trust that they would be adhered to without the threat of divine punishment. Maybe Moses made up the whole story about God on the top of Mt. Sinai for this purpose. I know I am skeptical when I hear tele-evangelists relate the messages they have heard directly from God.

The Ten Commandments that Moses brought down from Mt. Sinai might be divided into three groups. Four of them – Don’t kill, don’t steal, don’t lie, and don’t wish for what belongs to others – are practical rules that allow people to live in a peaceful, orderly society. I’ll call these the “Ethical Laws.” Three of them – I’m you’re only God, don’t create idols to worship, and don’t use my name in vain (this one is open to interpretation and will be discussed later) – don’t seem to have much to do with a civil society, but rather seem to cater to an egotistical, anthropomorphic deity. I’ll call these the “Loyalty Laws.” The final three – Don’t commit adultery, honor your parents, and remember the sabbath – could be interpreted as having more to do with culture, customs, and ceremony. I’ll call these the “Customs Laws.” To the extent that the last three overlap with the concepts of honesty, justice, kindness, or charity, or facilitate a peaceful orderly society, I would argue that the first four already have these covered.

I don’t think we need the threat of God’s judgment to know that we all make the world a better place when we refrain from killing, stealing, lying, and acting in an envious manner. Religious and non-religious people alike value high ethical and moral standards, and the actions of people like Donald Trump, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Lauren Boebert, Matt Goetz, Jim Jordan, Rudy Giuliani, Ted Cruz, Paul Gosar, Josh Harder, Mike Johnson, and Tommy Tuberville demonstrate that proclaiming a religious devotion does not exempt one from dishonesty and hypocrisy. Please feel free to add your own hypocrites to this list.

Today’s evangelical Christians in positions of power seem to violate the “Ethical Laws” so frequently and publicly that I was wondering if, unlike Romney, they either never took an oath with God or else don’t take that oath seriously. But lately I’ve come to realize that for them the “Ethical Laws” don’t really matter as long as they adhere to the “Loyalty Laws.” If one declares religious faith loudly enough, publicly enough, and often enough, then honesty, justice, kindness, and charity don’t matter. God will be flattered, forgive ethical sins, and reward those who praise him with admission to Heaven.

My maternal grandfather was a fundamentalist Lutheran minister in rural Pennsylvania. He and my grandmother taught my sisters, my cousins and me that the spirit of Jesus was always present and knew our every thought and action. I was six years old in 1956 when my four-year-old sister died from influenza. I remember my grandmother trying to comfort me by saying that she was so special that Jesus had called her up to Heaven to be by his side. I resented this nonsensical rationalization of death, and wondered if my grandmother really believed it. I know my mother did not. My mother later left the Lutheran church and became a Unitarian, where the “Ethical Laws” were all important but the “Loyalty Laws” mattered not at all to the clergy and the congregation. My father remained active in the men’s Bible study group at the Lutheran church, and later had me go through Catechism class and confirmation, but my path toward agnosticism had been set many years earlier. I remember being reprimanded in Catechism class for my less-than-serious attitude. My father and I never joined a church again after we moved to California when I was fifteen.

One cannot think about today’s practicing Christians without wondering about the various forms of worship and celebration there might be, the ways in which people people find strength from their faith, and the things that inspire them to believe. The Merriam-Webster dictionary offers three definitions of the word “faith”: 1 – allegiance to duty or a person; 2 – belief and trust in and loyalty to God; and 3 – firm belief in something for which there is no proof. Since atheists and agnostics don’t see any proof of the existence of God, they would see no difference between definition #2 and definition #3. So without empirical evidence of God, belief itself must provide strength and inspiration for the religious. When we see a sunrise we know that there is no golden orb tethered to the hand of God that he mystically lifts above the horizon, yet the faithful see the handiwork of God in every movement of nature. When some of us get news from the doctor that our potentially terminal disease has gone into remission, we are grateful to medical science, the efforts or our medical team, and our good luck. Others will declare that they have been blessed by God and praise his goodness and mercy. These people probably are not thinking of why their God has forsaken someone else who just saw the same doctor for the same condition and was told they only had a matter of weeks to live. Or they might simply say, “God works in mysterious ways.” Saying that God works in mysterious ways is the line that always emerges in the face of contradictory evidence for faith.

Faith in Christianity and the expression of that faith comes in many forms. People like our new Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, is said to be a Creationist, which means he takes the account of God’s creating Heaven and Earth, day and night, etc. in six days and resting on the seventh, literally. Others consider the stories in the bible to be nice parables, and gain inspiration from the words of Jesus, without having to believe in the virgin birth, the resurrection, or the promise of eternal life. Still others enjoy a lively, emotional celebration or simply enjoy the comfort of belonging to a congregation, hearing music on Sunday, singing in a choir, or listening to an intelligent, thoughtful, inspiring sermon. I assume that the majority of practicing Christians fall somewhere in between, not believing the literal creationist stories, but believing that there is salvation through believe in Jesus Christ and following his teachings. But honestly, I have no way of knowing this for sure, and I think it would be hard to honestly survey a representative sample of Americans to find out their true religious beliefs. I suspect that many individual’s beliefs are not fixed, either, but can change from day to day. Suffering and grief are powerful factors that keep people tied to a belief in Heaven. If one has lived an impoverished life or experienced chronic illness and pain, why not hope for a reward beyond Earth. And if one has suffered the loss of a loved one, the thought of being reunited with that person beyond the grave can be comforting. On the other hand, there are people who have died before us who have made our lives miserable on Earth. Will we have to suffer them when we encounter them again after we die? The thought of life everlasting itself can be frightening. I imagine a cartoon of a soul in Heaven sitting on a curb with his head in his hands and a choir of angels and a band of trumpeters behind him as he says, “Dear God, is there no end to this eternal basking in glory?”

If God does work in mysterious ways, who are we to assume that our good fortune, or bad fortune, have anything to do with those mysterious ways? My disbelieving self until recently was content to let the religious hang on to their faith unchallenged. When my non- belief was confronted by one of the faithful, my response was usually, “I’m glad you have your faith, but it just doesn’t work for me.” But lately I’m more likely to push back a little harder, depending on why someone might be wanting to interrogate me on religion. As an increasing number of politicians propose and even pass legislation that imposes Biblical law that has nothing to do with “Ethical Laws” on the American people, I believe it is time for people like me, who have politely kept their doubtful views to themselves, to speak up. If we were all more outspoken, I think we’d find that there are a lot more people than we assume who don’t buy into the Christian point of view (or any other fundamentalist view).

If closet non-religious people are more prevalent than the general public thinks, we should ponder why they remain closeted. People who run for office must believe that, unless they come from the most progressive of districts, they can’t get elected if they don’t have some kind of religious affiliation. Other religious skeptics fear that many Christians equate religiosity with morality, and fear that they will be viewed suspiciously, even thought to be immoral, if they deny religion. Others may hold on to the slightest superstition, thinking that even though the virgin birth, the miracles, the resurrection, and the promise of life everlasting don’t make much sense, just in case the threat of Hell is real they will not declare their doubts. Still others may say they don’t believe in any conventional religion, but they just can’t comprehend nothingness. Of course agnosticism and atheism are not synonymous with nothingness. Religious skeptics are open to the infinite mysteries of the universe. The more science learns about the origins of the universe, the solar system, our planet, and life on our planet, the more we realize how much greater the mystery really is. If there were a deity responsible for creating all this, it would be an insult to conceive of him as the anthropomorphic being described in Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Etc. In some ways, I like the approach Iris DeMent has taking in her song, “Let The Mystery Be,” of which there are many recorded versions. Of course, this doesn’t mean we should suspend our scientific inquiries, but we need to refrain from imposing simplistic, superstitious, disproven explanations on the American people.

I said I would discuss more about God imploring Moses to forbid the Israelites from taking his name in vain. Exodus 20:7 says, “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in Vain; for the Lord will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain.” I was raised to believe that this meant using the word “God” in a curse, such as saying “God Damn It,” a frequent utterance from my father. Now I believe that to be a trivial interpretation of that commandment, and I think that most conservative Christian politicians and Christian nationalists violate this commandment all the time. My interpretation is that to use God’s name in vain is to say you are speaking or acting on behalf of God when in fact you are acting in pure self interest, or using God’s name to deceive, manipulate, mislead, scare, or anger people. When these people tout their own righteousness, assert the godlessness of their opponents, tell you what God wants for our country, or that their actions are motivated by a deep faith, they are using God’s name in vain. They do not exist any closer to God, or have any greater insight into God’s will than you or I do when we ask ourselves how an honest, just, kind, and generous person should act. And since their behavior leads me to believe that honesty, justice, kindness, and generosity are not values they honor, I believe their every actions are acts of vanity. And yes, I am talking about the likes of Donald Trump, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Lauren Boebert, Matt Goetz, Jim Jordan, Rudy Giuliani, Ted Cruz, Paul Gosar, Josh Harder, Mike Johnson, and Tommy Tuberville. It would be easy to add another fifty or sixty names to this list.

“Don’t Tread On Me” has become the pet slogan of the 2nd Amendment zealots. In my neck of the woods I see lots of pickup trucks with this phrase printed on a yellow decal with a coiled rattlesnake. This is often next to another sticker that says something like, “When you come for mine, you better have yours.” The right wing has done a good job of convincing its followers inaccurately that sensible gun laws would mean all guns would be outlawed. But is America now facing a real, and quite different threat from the Christian Nationalist movement? Women are losing the right to control their own reproductive organs. Books in our libraries and schools are being banned. Scientific subjects that contradict biblical accounts of creation are being called into question. Funding for secular public schools is being cut. Laws are being proposed that would make it a crime for two consenting adults to engage in a loving relationship. These changes are based on a misunderstanding and misreading of a single book compiled from many writings over a long, long time to which divine origins are wrongly attributed. As a non-religious person with progressive political views, I feel as though a new wave of conservative politicians are treading on me, and sadly, people like me are too naive, trusting, and polite to recognize it, admit it, and speak out against it. We are not doing enough to ensure that in a democratic way, it goes no further than it already has.

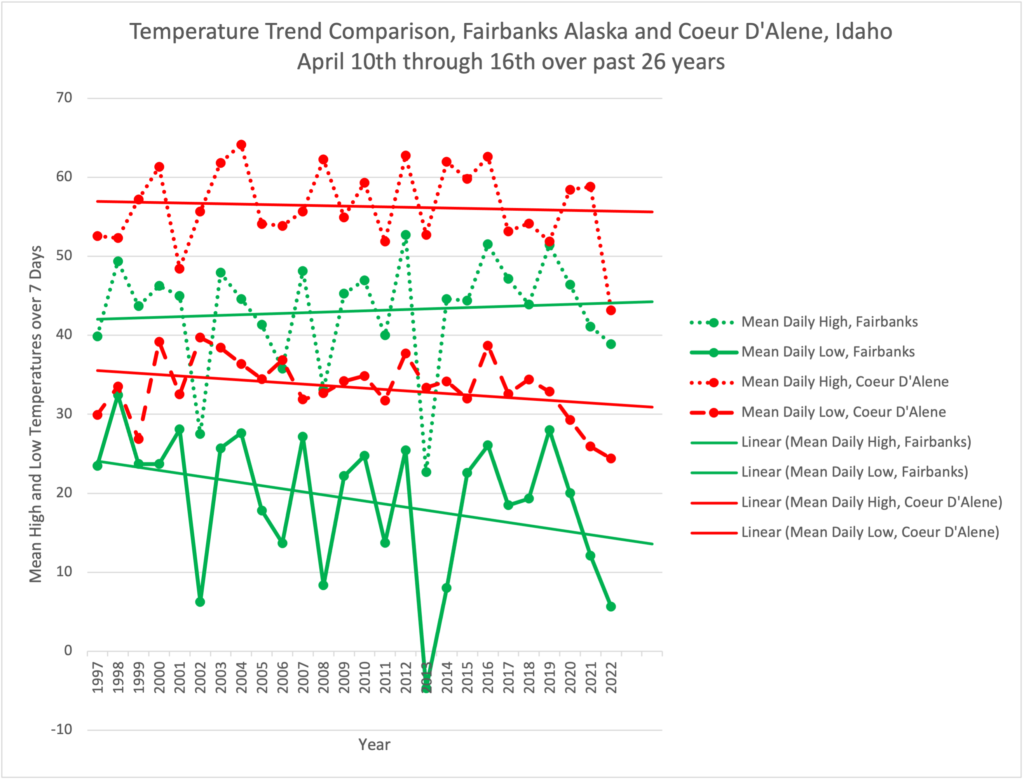

The “God” that these Christian Nationalists claim to bow to, and the one of which I am declaring my skepticism, is the one that has many contradictory profiles in the Bible. But even the most confirmed atheist must concede that we are governed by higher powers. If we think of these powers as godlike, then, speaking for myself, I took an oath before a concept of god on the day I was born. In accepting life I accepted the gravity that keeps me tethered to my planet. I accepted the oxygen that fuels my muscles and my brain. I accepted the cycles of seasons and days, of rain and sunshine, of bounty and famine. I accepted the need for water and nutrition, and I accepted the temperature limits outside of which I could not survive. I did not have to acknowledge these things, for by simply living I was making good on this oath. There is no promise that our Earth will sustain life forever. We know it won’t. But human behavior is increasing the odds that the Earth will be less able to sustain life in a matter of generations, rather than in a matter of ages, epochs, or periods of time.

I hope that people who share a concern for our planet’s ability to sustain life recognize the unspoken oath we have taken, and the responsibility that places on us. We have to oppose laws and values that don’t recognize, and in fact even deny this responsibility. We must support each other in standing for the values of honesty, justice, kindness, and charity, and oppose those who want to govern us based on an archaic vision of God. If fundamentalists want to believe in a literal interpretation of the Bible, let them do so. But they do not have the right to transform our country into one that conforms to their views, or oppressively subjects America’s citizens to their views.